A Note From the Author

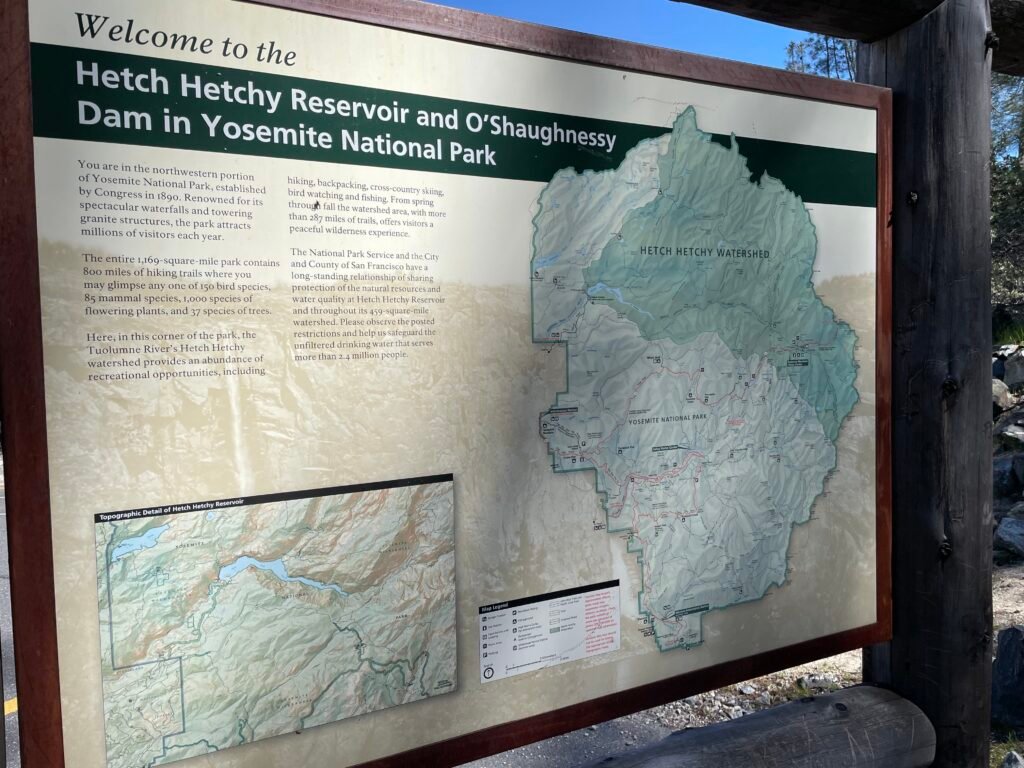

The following is a research paper I submitted for an American Environmental History class back in 2018, unedited except for the section subheadings and photographs. It covers a fight still raging today within environmental circles: should natural resources of significant beauty be left in a pristine state for people to explore, or should they be carefully utilized to benefit larger society. This came to a head in the still-controversial story of the only time a major industrial project was given the thumbs-up inside an already-protected bit of land in American history. Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley today provides some of the purest drinking water in the world to the California’s Bay Area, at the cost of burying a place that rivaled Yosemite Valley in terms of beauty under hundreds of feet of concrete and water. Here is the story of how that happened:

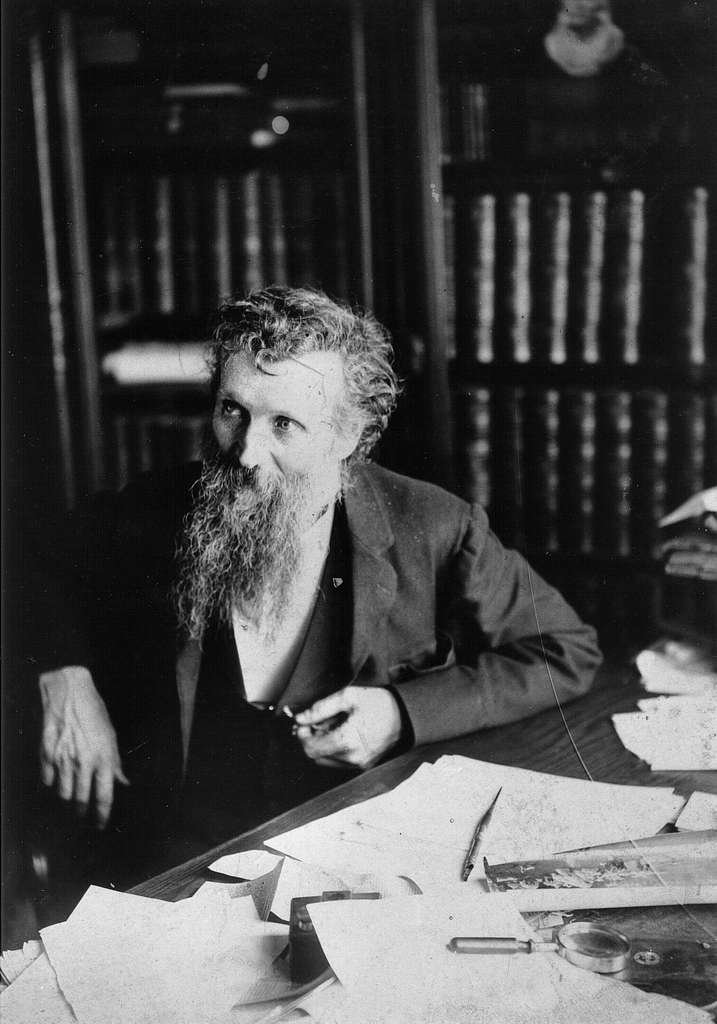

John Muir

“Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.”[1] Nature lover John Muir exclaimed this in 1912 as the competing ideologies of conservation and preservation of nature came to a clash over a proposed dam in Yosemite National Park. Presented as Document 3 in the chapter on “Wilderness Preservation in the Twentieth Century” in Major Problems in American Environmental History, I found his words fascinating and the story of Hetch Hetchy Valley equally fascinating, making this a good document to choose for this paper. The proposed dam would dam the Tuolumne River in the Hetch Hetchy Valley, further described by Muir as “one of nature’s rarest and most precious mountain temples, with its own majestic waterfalls and massive granite faces, it has all the beauty of the more famous Yosemite Valley, 20 miles to the South, without all the clutter of tourist hotels.”[2]

Who was John Muir and why did he feel so strongly about this valley? This is an interesting question to unpack before covering what went down in Hetch Hetchy. Muir was born not in America, but in a small town in Scotland called Dunbar on April 21, 1838. His family soon immigrated to the United States and he grew up on a family farm in Wisconsin. In his 20’s, from 1861-1863, he spent two years at the University of Wisconsin, where he studied chemistry and geology. After leaving the college, he started to travel extensively, developing a nearly unrivaled appreciation for nature along the way.

He visited his favorite spot, the Sierra Nevada mountains in the Western United States, for the first time in 1868. He first glimpse Yosemite Valley that year, which had already been protected by the United States by way of a bill passed by Lincoln during the Civil War.[3] Following that, he worked as a guide in Yosemite in between trips elsewhere, mapping the region and studying the animals and plants. With Yellowstone becoming the first national park in 1872, Muir launched a writing career that would bring about a great deal of public support for his preservationist goal for nature. Starting in 1874 with Studies in the Sierra, a scientific group of articles studying the mountain range, Muir became noticed by the public.[4]

In 1892, he founded the Sierra Club, a group of people dedicated to preserving nature in its pristine, unaltered form. This became a legitimate almost political lobbying group, one that would have great impact later on in the fight for Hetch Hetchy. In 1903, president Teddy Roosevelt requested Muir to guide him on a tour of Yosemite while he was out West. He lobbied with Roosevelt to take greater steps to protect the park federally, as the Yosemite Valley was controlled by the state even though the surrounding area was made a national park in 1890.[5] This was a success, and Muir thought he had saved Yosemite and its surrounding areas from development.[6]

In 1871, three years after entering Yosemite Valley, Muir had traveled nearby Hetch Hetchy Valley, similar to the more famous Yosemite Valley in that it was surrounded by granite cliffs and had multiple waterfalls; the ground was a large meadow for the most part. He was quick to compare the two valleys, even more so once the city of San Francisco began to show greater interest in it as a potential water supply following the Earthquake of 1903. The last years of his life were characterized by a noble, determined, yet ultimately doomed fight to save Hetch Hetchy from being dammed. Haunted by his failure to save his beloved valley, he died in 1914 of pneumonia, at the age of 76.[7]

The Frontier Arrives; San Francisco Booms

The story of Hetch Hetchy Valley itself precedes European arrival, even if the story of the Native Americans living in the area is often forgotten, a recurring theme in United States history. A group of tribes collectively known as the Central Miwok frequented the valley as a home during certain portions of the year.[8] But the valley was abandoned as the Native tribes were forced onto reservations during the latter half of the nineteenth century. The valley was largely enjoyed by tourists to Yosemite, more so once it became a part of Yosemite National Park when it was founded in 1890.

Yet with immigration and emigration on the rise, San Francisco’s population continued to explode, San Francisco needed a new supply of water. Mayor James Phelan, elected in 1896, set his eyes on pure water that could be found in the Tuolumne River in the Sierra Mountains. The ideal spot for a dam, it was determined, was Hetch Hetchy Valley, inside a protected national park. Phelan first applied to Department of the Interior, which at the time was managing the national parks, for permission for San Francisco to develop the valley into a reservoir and dam. Despite other viable alternatives, even some suggested by Muir, the proponents of the Hetch Hetchy Dam became fixated with the idea of that valley being the site of the dam.[9]

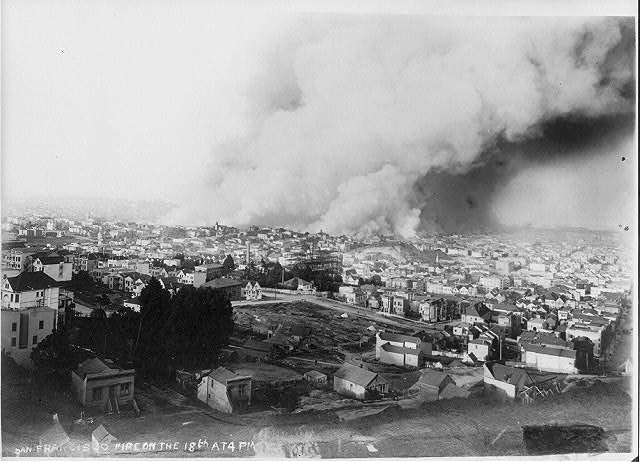

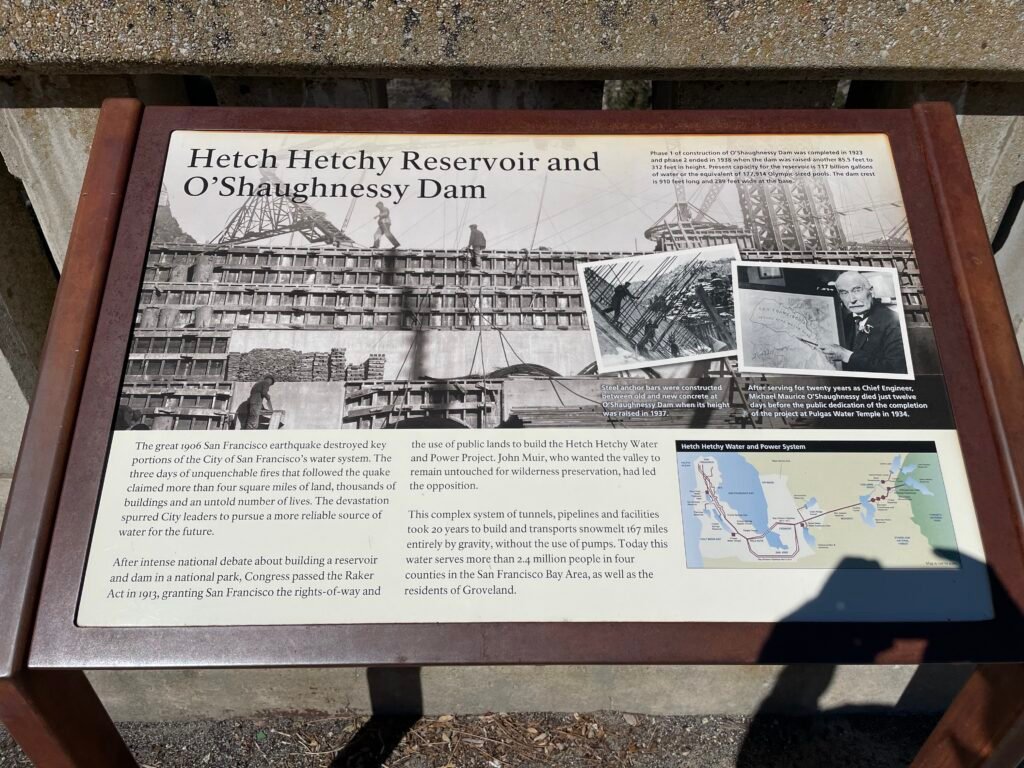

The Earthquake of 1906 in San Francisco saw a fire break out in the aftermath. The fire lasted for four days since the pipes to the city’s water system had broken in the aftermath. Despite this rendering any supply of water meaningless, the lack of water during the disaster to quell the fire was used by the pro-dam group as a prime reason San Francisco needed Hetch Hetchy to be turned into a reservoir. This only increased Phelan’s drive to succeed in his goal.

The Feds Take Notice

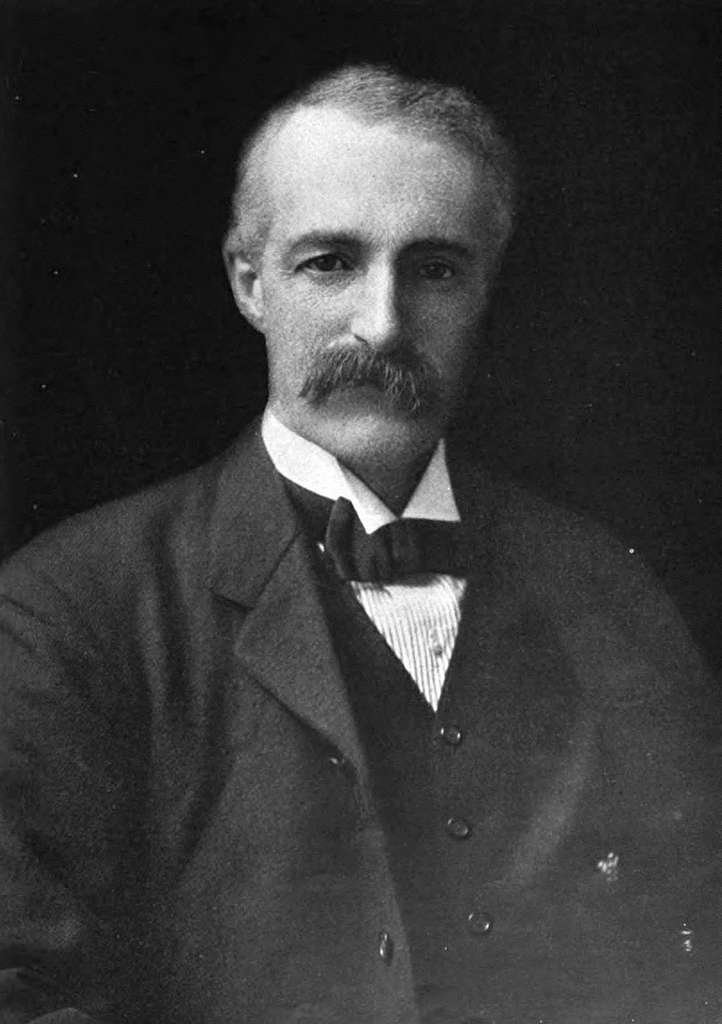

Throughout the struggle, John Muir and his Sierra Club were staunchly against doing anything but preserving Hetch Hetchy, as the designation of a national park was supposed to do. Muir became vocal about the matter when he started to realize that San Francisco politicians were moving ever closer to succeeding. He even had a falling out with a fellow lover of the outdoors, who, like Muir was dedicated to doing what he felt was best for natural landscapes: Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot, a conservationist who was a staunch advocate for the use of natural resources in smart measures to benefit the people, was for building a dam, which was to be the end of his relationship with Muir; Muir claimed, “Pinchot seems to have lost his head in coal and timber conservation and forgotten God and his handiwork.”[10]

Muir’s 1903 trip around Yosemite with President Teddy Roosevelt had gone a long way toward influencing Roosevelt to become a preservationist. When a new Secretary of the Interior and ally of Gifford Pinchot, James Garfield, took office in 1907, Muir reached out to Roosevelt asking for his assurances that he would protect the valley at all costs. Roosevelt gave Muir a lukewarm politician’s answer, saying that he would like to leave Hetch Hetchy untouched, but Muir needed significant support for him to be willing to stand in the way of a possible dam if it came to that point. John Muir got the point: he threw himself into drumming up public support for preserving the valley. At one point during the fight, he had support from newspapers from a staggering array of influential cities: New York City, Boston, Philadelphia, Mobile, Denver, Lincoln, Milwaukee, and Minneapolis.[11]

As Roosevelt left office in 1909 and was replaced by William Howard Taft, John Muir worked hard to win over the new president to his side in the fight over Hetch Hetchy. After San Franciscans got through a permit to build a dam, both sides argued their case in front of the House Committee of Public Lands. One of Muir’s main rivals, San Francisco mayor James Phelan got heated during this hearing and said about Muir, “I am sure he would sacrifice his own family for the preservation of beauty. He considers human life very cheap, and he considers the works of God superior.”[12]

Proponents of the dam were annoyed when Taft, like Roosevelt, chose Muir to tour Yosemite, and Hetch Hetchy Valley, with him in 1909. Like before, Muir was heavily influential and convinced Taft to protect the valley. Responding, San Francisco attempted to turn the tide of public opinion. Hiring a group of engineers headed by a man named John Freeman, they put together a 401-page publication that showed their “evidence” how damming Hetch Hetchy would actually make the valley more beautiful by allowing for a large, clear lake with easier road access instead of having to hike into the valley, as was the case at the time. Using pictures of European reservoirs that supposedly “enhanced” the beauty of the land, San Francisco attempted to appeal to and sway the crowd they had been fighting against.[13]

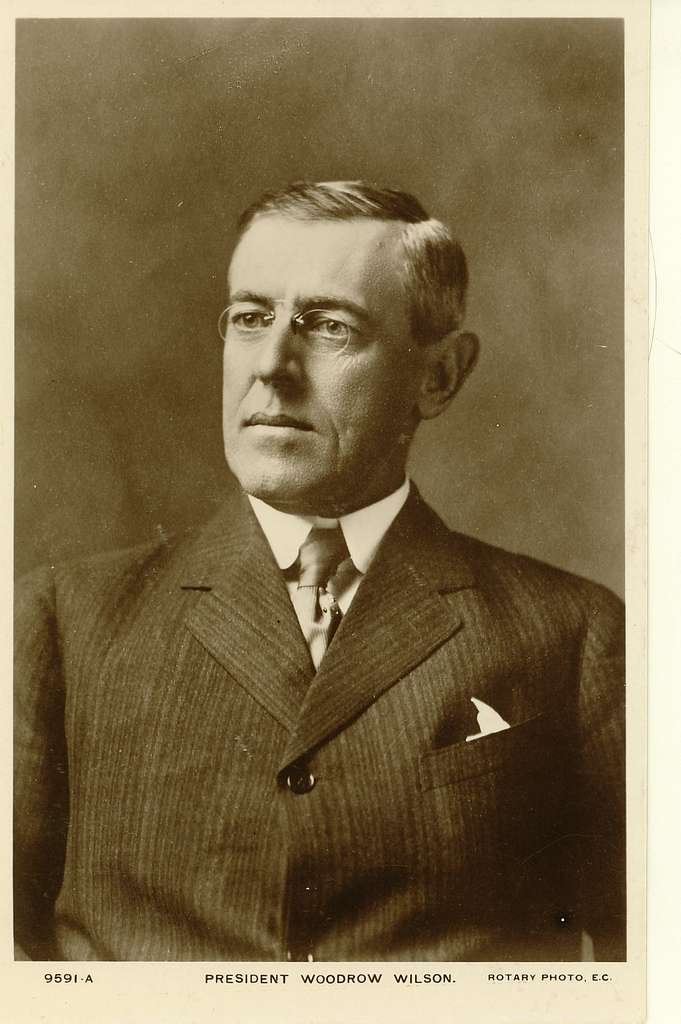

The back and forth continued without anything decisive until after Taft left office. Woodrow Wilson took office in 1913, a Democrat whereas the prior two presidents were Republicans. He selected a new head for the Department of the Interior, Franklin K. Lane, who had worked as an attorney for the city of San Francisco under James Phelan and was very much pro-dam.[14] From there, despite the protests of Muir, the Sierra Club, and their allies, things snowballed in favor of building a dam. After Lane gave his approval on getting San Francisco a permit the decision went to Congress. With most of the House on vacation, the proposed dam bill passed controversially, and the Senate went on to approve the bill as well.[15]

The Decision, 1913-Style

Woodrow Wilson passed the dam bill, now known as the Raker Bill, on December 19, 1913. The bill states in its heading all Muir fought against: “An act granting to the city and county of San Francisco certain rights of way in, over, and through certain public lands, the Yosemite National Park…and the public lands in the State of California”[16] With that, Hetch Hetchy Valley was condemned to be submerged underwater, a reservoir to provide the citizens of San Francisco with clean water. Construction started in 1915 under engineer Michael O’ Shaughnessy and lasted much longer than expected, until 1934. O’Shaughnessy Dam, the dam in the valley, is named after him to the day. The cost of the dam would total upwards of $100,000,000, which was over two times the amount expected when the Raker Bill was passed in 1913.[17]

Hetch Hetchy Valley ended up submerged, but John Muir’s sharp words in 1912 were not soon forgotten. The preservation vs. conservation debate raged, but no large-scale development has happened in a national park since the Raker Bill was passed over 100 years ago. When the government once again tried to dam a portion of Colorado River inside Dinosaur National Monument in Utah, the Sierra Club picked up Muir’s mantle and went to fight once again for saving the natural landscape within a national park. David Brower, the executive director of the Sierra Club in the 1950’s, went public with a campaign to save Dinosaur and to avoid repeating history. He succeeded where Muir hadn’t in his final battle, swaying public opinion in favor of preservation and keeping the dam out of the areas in and near the national monument.[18]

In addition, the National Park Service was founded shortly after the Raker Bill passed, to protect and oversee the national parks. Woodrow Wilson passed the bill creating the service on August 15, 1916, less than three years after the final decision on Hetch Hetchy. A part of the Department of the Interior, the National Park Service was initially headed by Stephen Mather, a preservationist in line with John Muir who worked to protect the landscapes in national parks from any further intrusion.[19]

It turns the battle over the valley still goes on today, and so does the fight to preserve and conserve nature. A court case is going on currently, filed by a group called Restore Hetch Hetchy that consists of people dedicated to getting rid of the reservoir and O’Shaughnessy Dam and returning the valley to its initial state. The case says the O’Shaughnessy Dam violates California law because there are other ways to store water in the area and that the city of San Francisco violated the Raker Act by selling the water supply to a private company to profit off.[20] The dam still stands to this day, however, as the only major intrusive development inside a national park, and nearly all of San Francisco’s water supply still comes from it.[21]

Ongoing Debate

I find it particularly fascinating that the two sides, conservationists and preservations, from over one hundred years ago often are on the same side today, with big corporations defiling the land and resources in instances such as the Dakota Pipeline. The environmental fight continues now goes well beyond a dam in Yosemite; with climate change and vanishing resources the need is more urgent than ever to band together to save our precious planet. It will take a great amount of effort, as we discussed in this class.

I also find it fascinating how, despite the fears of John Muir and other environmental advocates, the damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley did not set a precedent; instead it became an outlier. Muir’s warning about the potential loss of our last untouched lands had clearly been headed to a degree, and national parks have gotten greater protection, as he called for in the document. Although we aren’t always all that great when it comes to dealing with the environment, we are doing a much better job I feel.

“These temples destroyers, devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature, and, instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the mountains, lift them to the Almighty Dollar.”[22] John Muir’s 1912 quote still holds a lot of relevance and causes one to pause. While the almighty dollar still rules our society as Muir saw it did back in the day, we have done a much better job appreciating the natural world than showing contempt for it. At the very least, I think this would have provided Muir hope that we as a country can keep doing better.

A collection of photographs taken by the author on a trip to Hetch Hetchy in 2024

Bibliography:

Merchant, Carolyn. Major Problems in American Environmental History: Documents and Essays. Boston, MA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning, 2012.

Steinberg, Ted. Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Fox, Stephen. The American Conservation Movement: John Muir and His Legacy. Madison, Wisc.: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1985.

Swift, Hildegarde Hoyt. From the Eagle’s Wings. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1962.

Righter, Robert W. The Battle over Hetch Hetchy: Americas Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. Accessed December 7, 2018.

Macdonald, Glen M. “John Muir: A Century On.” Boom: A Journal of California 4, no. 3 (2014): 60-69. doi:10.1525/boom.2014.4.3.60.

Holliday, J. S. “The Politics of John Muir.” California History 63, no. 2 (1984): 135-39. doi:10.2307/25158207.

National Parks: America’s Best Idea. Directed by Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan. United States: Florentine Films, 2009. DVD. Accessed December 7, 2018. http://fod.infobase.com/p_ViewVideo.aspx?xtid=44453.

Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. Accessed December 9, 2018. http://www.sfmuseum.org/hetch/hetchy10.html.

Rogers, Paul. “Environmentalists’ Lawsuit to Drain Hetch Hetchy Reservoir Heads Back to Court.” The Mercury News. May 30, 2018. Accessed December 9, 2018. https://www.mercurynews.com/2018/05/29/environmentalists-lawsuit-to-drain-hetch-hetchy-reservoir-heads-back-to-court/.

Chinn, Harvey. “Biographical Timeline of John Muir’s Life.” Sierra Club Vault. Accessed December 7, 2018. https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/john_muir_day_study_guide/biographical_timeline.aspx.

Footnotes

[1] Carolyn Merchant, Major Problems in American Environmental History, 371

[2] National Parks: America’s Best Idea, Episode 2

[3] Hildegarde Hoyt Smith, From the Eagle’s Wing, 130

[4] Sierra Club website timeline

[5] Holiday, Politics of Muir, 138

[6] Righter, The Battle over Hetch Hetchy: Americas Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism, 11

[7] Biographical information from From the Eagle’s Wings

[8] Battle over Hetch Hetchy, 16

[9] Battle over Hetch Hetchy 52

[10] Macdonald, Muir: A Century On, 63

[11] Politics of Muir 158

[12] Fox, The American Conservation Movement: John Muir and his Legacy, 142

[13] Battle over Hetch Hetchy 102

[14] Battle over Hetch Hetchy 118

[15] From the Eagle’s Wing 274-275

[16] Raker Act, text obtained from website of Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

[17] The American Conservation Movement 146

[18] Steinberg, Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History, 224

[19] American Conservation Movement 146

[20] Mercury News article, “Environmentalists’ Lawsuit to Drain Hetch Hetchy Reservoir Heads Back to Court”

[21] Battle over Hetch Hetchy 236

[22] Major Problems 371

Great article! I enjoyed the back and forth between the preservationist and conservationists but with most debates I believe a little give and take will put both parties in the middle which will work out best for all concerns assuming one party is not off the deep end. Unfortunately, most opposite party discussions are not willing to give and take. It is their way or the highway. Sad! I would like to discuss this with you when you have time.

I agree that compromise is sadly becoming a lost art – totally down to discuss!

This is super informative and I’m glad that paper came in handy! I’m sure you got an A because I learned a lot here.

Thank you for the explanation of what happened.